Regular visitors to this parish will acknowledge that hackneyed phrasing is a given, so here goes with another oft repeated line:

Crikes! where did all the water go?

I can feel another bit of hackney coming on,

I can't believe the speed at which the river has dropped during the past month.

You will be aware of a disregard for official figures particularly those regarding quantity and quality of water, because they are mostly made up, or adjusted to suit some other agenda (normally big business and the bottom line) But here's a FACT (Thank you to Rafa Benitez for ensuring that this word is now forever written in capitals) if we were still using our earth ponds to produce brown trout, the fish would have been moved elsewhere several weeks ago because there isn't enough water for the ponds to function as a unit for rearing salmonids. The twelve inch pipe that used to feed water through to the fish is higher than the water level of the river.

This has not been the case during my time falling in and out of this river.

Hackneyed phrase number three is imminent,

We need a lot of rain in the south this winter.

Thankfully the wallahs at command centre central are on to this and last week issued a press release warning of a diminishing water supply in the south of England and could we all be a little less profligate with the old eau.

Although we are now entering the silly season regarding rain with DJ's and Journos bemoaning a grey day and drizzle and don't expect anyone to put a positive spin on a spell of wet weather in the south of England at any point this winter.

Fishing remains hard. I was kindly invited to fish the Anton earlier this week and goodness the fish were spooky. I managed a couple of grayling off the top on a red tag but like here on the Dever most fish were bunched up in holes, spook one and they all go off in a nervy spaz.

Fish have been caught this week including one brown trout of two and a half pound that had the body length of a three pounder, which is a worry as there shouldn't be thin fish about at this time of the year. Hatches of fly early on in the season were reasonable although like Liverpool of late with their high energy pressing game they have tailed off a tad during the second half.

We still have House Martins about, although most of the swallows and swifts have exited stage left and we also have an early egret stalking the shallows. We retain a quorum of swans, but not far downstream several beats have been hit hard by high numbers of Gielgud who played fast and loose with river restoration work and much replanted ranunculus has been plucked from the river bed.

All this river restoration work driven by habitat directive is highly commendable and hopefully the funding will continue to be available post Brexit but forgive my ignorance, as I am but a stupid riverkeeper, but shouldn't a holistic approach to habitat management attend to all areas of the chalk stream environment.

Which brings me to a tale to rival the Court of King Caractacus that began with a Fishery Management Consultation (expert advice for no little fee and brim full of your rewilding) upstream from here five or so years ago and will hopefully reach a conclusion following a meeting with some big noises from command centre central in a few weeks time. I'll not furnish you with the details just yet as I'd prefer to keep my powder dry for said meeting in early October. But it concerns the dramatic decline in numbers of sexually mature fish of all species in the river.

I'll report the outcome of what will hopefully be a productive meeting, early next month and the river's fish population will make preparation to return to the level recorded in command centre central surveys five or so years ago.

Oh yes, the storm.

A tremendous panjandrum that rolled around the valley for four hours one night last week. Many parts missed it, but for the following twenty four hours the river ran eight inches higher and assumed the colour of the Grand Union Canal. Not the best kind of rain as not much gets down into the aquifers, lots of branches were forced to dip and bow and a day later all the water had flowed away (Oh for a series of hatches to retain water on a meadow to soak back into an aquifer) but quite a weather event (I believe this is the current meteorological parlance) all the same.

In other news, I was once again required to cook a pig for the cricket club presentation evening, which to date, passed without serious illness, and we received news that my parents had been press ganged in the back streets of Glasgow and were held on a boat making its way east along the English Channel. We intercepted the sloop and boarded at Portsmouth. It was quickly established that they had in fact signed up of their own accord.

We took rum and hard tack

but then scurvy set in

and we were forced to seek out some vitamin C/cake/sausage rolls/ prawns in batter for dippin.

They were on a Saga cruise to infinity and beyond, and we were invited aboard as guests.

They're a canny bunch the Saga crew, our clubcard points , internet history or some other paper trail has betrayed the fact that we are only eighteen months away from qualifying for membership of the club and are trying to tempt us with a ship full of food.

At home, Child A has purchased a pink car and continues her work for Thames Valley Police. It sounds a little gritty at times, especially the Saturday night shift, although there are lighter moments. I don't think I could do it, as I am sure that with a distraught person on the other end of the phone I'd try to lighten the mood a little with some such nonsense or other, which is not what is required apparently.

Child B has transferred to Cardiff for his final year. Here he is on the left with the rest of his Cardiff crew climbing a mountain in Wales. It's a bit like Inbetweeners do Wainwright, with neither a carabiner, compass, freeze dried food or survival bag in sight.

This is not how I remember scaling mountains in Wales,

Welsh mountains may not be as high as they used to be.

The lady who sleeps on my left has just returned from the biennial school trip to Highclere castle with the scathing indictment,

"They couldn't give a fig about school trips ticking the Egyptology curriculum box now they've got Downton"

So keep an eye out on ebay for treasures from Tutankhamun, particularly from the seller 1922Carnavon

And there we go, two weeks left of the season and a long list of tasks and trees to be attended to this winter. We've a couple more trips away to look forward to in coming months, one of them complimentary, and at that this point I'll warn you to expect a hard sell for a particular establishment in the coming months. For the purity of the piece I've turned down several requests to place adverts in and around this guff,

but with the years proceeding and an erratically performing personal pension pot (more of a crucible than a pot) I've sold my soul for a complimentary overnight stay with dinner and breakfast in one of Dublin's top hotels in Temple Bar (the pitch starts her folks) to take in David O'Doherty (one of our favourite comedians) at Vicar St Theatre (one of our favourite venues, no really, that last bit was sincere it is a terrific place to watch comedy) later this year - report to follow.

Saturday, 24 September 2016

Tuesday, 13 September 2016

A whistle stop tour of the Ypres Salient

Further Parish Messages.

2: A report on our whistle stop tour to the Ypres Salient.

Like last year's overnight visit to the Somme I feel compelled to write something down, for my own sake if nothing else as I don't want to forget.

You may agree with what you are about to read, you may not,

I'm not particularly bothered either way as this is an honest account of how I felt twenty four hours after our visit to the fields of Flanders.

A little self indulgent perhaps but no clever conclusions or judgement with the benefit of hindsight, just my own observations on a region that few could fail to be touched by.

Lord and Lady Ludgershall would once again be our eminent and excellent guides and we pitched up in Calais a little before 9am. Provisions were purchased in Auchan before we made haste through the hops for Poperinge, the gateway to the Ypres salient and headquarters for much of the war machine operating on that part of the Western front.

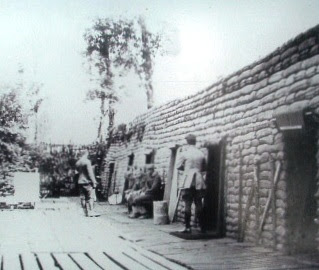

It also served as a site for soldiers on a break from time in the front line or in reserve and it was to Talbot House that we headed first. Founded by the Reverend Tubby Taylor it served as an "Everyman's club" for soldiers of all rank in the British Army and provided a brief sanctuary from the madness that is the business of war.

It is remarkably well preserved and still provides accommodation. The Garden in particular must have provided particular solace from an environment reduced to deep mud by bad weather and intense artillery fire.

There was a rudimentary cinema on the first floor and in the roof a tiny chapel. He sounded like a thoroughly decent chap did Tubby Taylor and was obviously highly thought of, as were most of the chaplains who spent time in the front line.

Out of Talbot House and after making brief acquaintance with a statue of Elaine Cossey, known as Ginger to soldiers from all corners of the British Empire for her red hair and vivacity she embodied for many a reminder of human dignity and life that they carried into the hell of the trenches as a spark in their hearts.

The town hall next and the cells where soldiers were held for all manner of misdemeanours including desertion and cowardice, the penalty for these two, being tied to the post that stands in the courtyard and a bullet through the head at dawn. PTSD would be today's diagnosis for many who went this way, but at the time the army relied on Tommy Atkins having enough fire in his belly to climb out of his trench, brave the artillery, machine guns and gas and engage the enemy by whatever means possible, be it rifle, bayonet, club or spade,it was a brutal business maintained by, at times, brutal discipline in an age disparate from today.

Off to Ypres next, a city at the heart of the bulge in the Western Front known as the Ypres salient. It started the war as the third largest city in Flanders after Bruges and Ghent and was dominated by the 13th century Cloth hall and like so many cities in the region was protected by 17th century fortifications by the much vaunted Vauban.

Unfortunately his bulky buttresses and clever ravelins proved no match for several years of Teutonic artillery bombardment from behind the low ridges that surround the city and by 1918 the city was reduced to a pile of rubble.

A million or more Flemish acquired refugee status when the war arrived on their doorstep and were forced to cross international borders to escape the conflict.

Many went to Holland, some went to Britain, others went to more peaceful parts of France.

When the armistice was signed some stayed where they had ended up, but most returned to where they lived before war broke out.

The British called for Ypres not to be rebuilt and stand as a memorial of the many battles that had taken place there, but the Flemish had other ideas and rebuilt the city as it had stood before the bombs began to fall.

And well done the Flemish for that.

I'm not really religious, but there is merit in a resurrection and after the madness of war has receded more than a modicum of faith in humanity is restored when your everyday Joe and Josephine emerge from the wings to pick up the pieces,no matter how shattered the vase.

Welcome to Ypres

It's a city that strikes the right balance between reverence and the requirement to move forward.

It is all too easy to forget that within Pandora's box, hidden beneath all the bad stuff, lay hope.

The Menin Gate straddling the Menin road down which so many trudged never to return stands as a fitting monument to the missing,

although the Last Post in tourist time in high heat was a bit of a scrum as it is an understandable box to be ticked on any organised tour of the area.

It may be more evocative witnessing the event on a bleak day at the end of October in conditions more familiar to the sixty thousand names on the gate.

Kicking back in Ypres, because yes, it is not a maudlin place. We devoured a fine repast ( Flemish stew, Moules, Shrimp Croquettes, Steak and no little wine) in a popular restaurant in the square before heading home to bed.

After the conventional European breakfast we headed to the In Flanders Field Museum housed in the rebuilt Cloth market.

It's a very good museum.

We shared the place with people from many nations who fought on both sides of the war.

As well as the excellent and informative exhibits, it is worth paying the extra two euros to climb to the top of the clock tower which provides an excellent view of the city and the route out of town to the front line and the low ridges held by the Germans.

It takes two hours to do the museum and pick your time to climb the tower as during the rebuild they installed a clever carillian that strikes every fifteen minutes. It's an elaborate series of gongs to signal the passing of time and the stairs to the top pass within a few feet of the many bells, Lord Lugg timed his run wrong and had sparrows circling his crown (see The Beano) for quite a few minutes.

Heading out of town, it was off to Essex Farm and the advanced dressing station where the Canadian Medico John McCrae wrote "In Flanders Fields" after witnessing his mate obliterated by a direct hit to the artillery battery to which he was assigned on the bank of the nearby canal.

We visited McCrae's grave on our trip down the coast to Etaples last year. Madam's school use the text each year when the curriculum requires them to make mention of the First World War. How McCrae came up with such easy prose in the most desperate of circumstances is beyond me, but then I refer you back to the top of this guff, it is impossible to comprehend what was possible in such circumstances with the benefit of hindsight.

Vancouver corner next and a stunning art deco memorial of a brooding soldier that marks the site where a Canadian division were subject to one of the first gas attacks during the second battle of Ypres

.The designer of the memorial had finished second in a competition to the chap who came up with the Vimy Ridge memorial.

The Vancouver corner memorial may be substantially smaller than the winner of the competition, but the impact is the equal of Vimy Ridge.

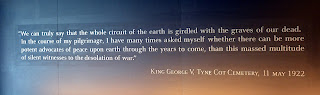

And so to Tyne Cot, the largest CWGC in existence on top of the Passchendaele ridge looking back across all those Flanders Fields to Ypres.

In preparation for our visit I'd read "Passchendaele" by Nigel Steel and Peter Hart. It's a good book that relies heavily on anecdote from those who were there, the German take on matters is a little lacking , but it is evident that men (a lot of whom had already been through the misery of the Somme) were operating at mental and physical limits difficult to comprehend today. Dreadful Weather and intense artillery bombardment rendered the field of battle close to impassable. The Germans held the higher ground and constructed a series of pill boxes that covered each other if attacked. The Allies adopted new tactics of "Bite and hold" with the objective of a decisive breakthrough abandoned they sought smaller gains of a thousand yards or so that they would then endeavour to retain in the face of the inevitable German counter attack. This was then abandoned briefly with disastrous results before a return to a more prepared approach under the command of a Canadian which was also doomed to fail in impossible conditions as the fields of Flanders became the very embodiment of hell.

A few words from one who was there

The approach to the ridge was a desolate swamp, over which brooded an evil menacing atmosphere that seemed to defy encroachment. Far more treacherous than the visible surface defences with which we were familiar; deep devouring mud spread deadly traps in all directions. We splashed and slithered, and dragged our feet from the pull of an invisible enemy determined to suck us into its depths. Every few steps someone would slide and stumble and weighed down by rifle and equipment, rapidly sink into the squelching mess. Those nearest grabbed his arms, struggled against being themselves engulfed and, if humanly possible, dragged him out. When helpers floundered in as well and doubled the task, it became hopeless. All the straining efforts failed and the swamp swallowed its screaming victims, and we had to be ordered to plod on dejectedly and fight this relentless enemy as stubbornly as we did those we could see. It happened that one of those leading us was Lieutenant Chamberlain, and so distraught did he become at the spectacle of men drowning in mud, and the desperate efforts to rescue them that suddenly he began hysterically belabouring the shoulders of a sinking man with his swagger stick. We were horrified to see this most compassionate officer so unstrung as to resort to brutality, and our loud protests forced him to desist. The man was rescued, but some could not be and they sank shrieking with fear and agony. To be ordered to go ahead and leave a comrade to such a fate was the hardest experience one could be asked to endure, but the objective had to be reached, and we plunged on, bitter anger against the evil forces prevailing piled on to our exasperation. This was as near to Hell as I ever want to be.

Private Norman Cliff. 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards.

The hope that sprung from Pandora's box is evident in the rebuild of Ypres, the desolation of war is all to evident at Tyne Cot. It is an affecting place sited on the low ridge looking back at Ypres across the Flanders fields in which so many met a miserable end.

You enter the cemetery on a path with hidden speakers through which the voice of a young woman issues a roll call of the dead. Most were around the age of my own children, which raised the first lump in the throat. Enter the visitor centre and a minimalist display draws the eye,

as do some quotes on the wall

but driven by the background roll call

the eye is drawn to a screen on the end wall displaying the photo of each person announced,

and at this point I nearly went because after all the grave stones, crosses and memorials there were human beings with their own identity and story to tell behind each set of eyes.

Here's a quote from one who made it home

"The next night my pal came out with me. We heard one of their big ones coming over. Normally within reason, you could tell if it was going to land anywhere near or not. If it was, the normal procedure was to throw yourself down and avoid the shell fragments. This one we knew was going to drop near. My pal shouted and threw himself down. I was too damned tired even to fall down. I stood there. Next i had a terrific pain in the back and chest and I found myself face down in the mud. My pal came to me, he tried to lift me up. I said to him, "Don't touch me, leave me, I've had enough, just leave me" The next thing I found myself sinking in the mud. I don't hate it any more- it seemed like a protective blanket covering me. I thought "well this is death, it's not so bad" Then I foudn myself being bumped about and realised I was on a stretcher. I thought "poor devils these stretcher bearers - I wouldn't be a stretcher bearer for anything" I suddenly realised I wasn't dead and that if these wounds didn't prove fatal I should get back to my parents, to my sister, to my girl who I was going to marry. The girl that had sent me a letter every day from the beginning of the war. I thought "Thank God for that!" Then the dressing station, morphia and the sleep that is so badly needed. I didn't recollect any more till I found myself in a bed with white sheets and I heard the lovely wonderful voices of our nurses. Then I completely broke down."

Bombardier J.W Palmer, 26th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery laying communication lines who had survived three years in action.

It is difficult to portray the scale of Tyne Cot with a camera from the ground so here's one from the air.

Many of the graves and names on the wall are of soldiers who travelled a long way around the world (when transport was not so simple as today) to fight the hun. Rows and rows of Australians, Canadians, Africans, Indians and corners of Europe that I had previously thought unaffected by the war.

And then it was time to go home.

The final display in The Flanders Field museum states that this was the war to end all wars,

it wasn't, and there is a list of every war that has taken place since 1918 above the exit.

It is important that we continue to remember and also retain hope that a future generation will adopt an alternative means of settling national or religious differences than through armed conflict

"Well then you ask, why did men apparently unhesitatingly go forward in attack and capture strongpoints sometimes with reckless bravery? The answer is simple - I must repeat that there is no alternative to the firing squad but to go forward and you do your damnedest to kill the men who are trying to kill you. If you do not, you just die. In all this fighting when trenches and strongpoints are captured you are not a hero - you are obeying not man's instinct to kill, but man's instinct to live by killing the man who would kill you. Those that believe in the inevitability of war will always emphasise that man has an inherent killer instinct, that it is human nature and little can be done about it.

Another "Old Lie" a perfidious Old lie.

Man is not born a killer, it is the society in which he grows up which makes him one and that society must continually reiterate the lie to justify the act of killing in war.

I never wanted to kill anyone,

but I did...."

Private W.H.A Groom 1/5th Battalion London Regiment (Rifle Brigade)

Clicks Playlist of Joan Baez, Bill Withers and Country Joe and the Fish and sits back slightly dumbstruck, but grateful never to have experienced war at first hand.

2: A report on our whistle stop tour to the Ypres Salient.

Like last year's overnight visit to the Somme I feel compelled to write something down, for my own sake if nothing else as I don't want to forget.

You may agree with what you are about to read, you may not,

I'm not particularly bothered either way as this is an honest account of how I felt twenty four hours after our visit to the fields of Flanders.

A little self indulgent perhaps but no clever conclusions or judgement with the benefit of hindsight, just my own observations on a region that few could fail to be touched by.

Lord and Lady Ludgershall would once again be our eminent and excellent guides and we pitched up in Calais a little before 9am. Provisions were purchased in Auchan before we made haste through the hops for Poperinge, the gateway to the Ypres salient and headquarters for much of the war machine operating on that part of the Western front.

It also served as a site for soldiers on a break from time in the front line or in reserve and it was to Talbot House that we headed first. Founded by the Reverend Tubby Taylor it served as an "Everyman's club" for soldiers of all rank in the British Army and provided a brief sanctuary from the madness that is the business of war.

It is remarkably well preserved and still provides accommodation. The Garden in particular must have provided particular solace from an environment reduced to deep mud by bad weather and intense artillery fire.

There was a rudimentary cinema on the first floor and in the roof a tiny chapel. He sounded like a thoroughly decent chap did Tubby Taylor and was obviously highly thought of, as were most of the chaplains who spent time in the front line.

Out of Talbot House and after making brief acquaintance with a statue of Elaine Cossey, known as Ginger to soldiers from all corners of the British Empire for her red hair and vivacity she embodied for many a reminder of human dignity and life that they carried into the hell of the trenches as a spark in their hearts.

The town hall next and the cells where soldiers were held for all manner of misdemeanours including desertion and cowardice, the penalty for these two, being tied to the post that stands in the courtyard and a bullet through the head at dawn. PTSD would be today's diagnosis for many who went this way, but at the time the army relied on Tommy Atkins having enough fire in his belly to climb out of his trench, brave the artillery, machine guns and gas and engage the enemy by whatever means possible, be it rifle, bayonet, club or spade,it was a brutal business maintained by, at times, brutal discipline in an age disparate from today.

Off to Ypres next, a city at the heart of the bulge in the Western Front known as the Ypres salient. It started the war as the third largest city in Flanders after Bruges and Ghent and was dominated by the 13th century Cloth hall and like so many cities in the region was protected by 17th century fortifications by the much vaunted Vauban.

Unfortunately his bulky buttresses and clever ravelins proved no match for several years of Teutonic artillery bombardment from behind the low ridges that surround the city and by 1918 the city was reduced to a pile of rubble.

A million or more Flemish acquired refugee status when the war arrived on their doorstep and were forced to cross international borders to escape the conflict.

Many went to Holland, some went to Britain, others went to more peaceful parts of France.

When the armistice was signed some stayed where they had ended up, but most returned to where they lived before war broke out.

The British called for Ypres not to be rebuilt and stand as a memorial of the many battles that had taken place there, but the Flemish had other ideas and rebuilt the city as it had stood before the bombs began to fall.

And well done the Flemish for that.

I'm not really religious, but there is merit in a resurrection and after the madness of war has receded more than a modicum of faith in humanity is restored when your everyday Joe and Josephine emerge from the wings to pick up the pieces,no matter how shattered the vase.

Welcome to Ypres

It's a city that strikes the right balance between reverence and the requirement to move forward.

It is all too easy to forget that within Pandora's box, hidden beneath all the bad stuff, lay hope.

The Menin Gate straddling the Menin road down which so many trudged never to return stands as a fitting monument to the missing,

although the Last Post in tourist time in high heat was a bit of a scrum as it is an understandable box to be ticked on any organised tour of the area.

It may be more evocative witnessing the event on a bleak day at the end of October in conditions more familiar to the sixty thousand names on the gate.

Kicking back in Ypres, because yes, it is not a maudlin place. We devoured a fine repast ( Flemish stew, Moules, Shrimp Croquettes, Steak and no little wine) in a popular restaurant in the square before heading home to bed.

After the conventional European breakfast we headed to the In Flanders Field Museum housed in the rebuilt Cloth market.

It's a very good museum.

We shared the place with people from many nations who fought on both sides of the war.

As well as the excellent and informative exhibits, it is worth paying the extra two euros to climb to the top of the clock tower which provides an excellent view of the city and the route out of town to the front line and the low ridges held by the Germans.

It takes two hours to do the museum and pick your time to climb the tower as during the rebuild they installed a clever carillian that strikes every fifteen minutes. It's an elaborate series of gongs to signal the passing of time and the stairs to the top pass within a few feet of the many bells, Lord Lugg timed his run wrong and had sparrows circling his crown (see The Beano) for quite a few minutes.

Heading out of town, it was off to Essex Farm and the advanced dressing station where the Canadian Medico John McCrae wrote "In Flanders Fields" after witnessing his mate obliterated by a direct hit to the artillery battery to which he was assigned on the bank of the nearby canal.

We visited McCrae's grave on our trip down the coast to Etaples last year. Madam's school use the text each year when the curriculum requires them to make mention of the First World War. How McCrae came up with such easy prose in the most desperate of circumstances is beyond me, but then I refer you back to the top of this guff, it is impossible to comprehend what was possible in such circumstances with the benefit of hindsight.

Vancouver corner next and a stunning art deco memorial of a brooding soldier that marks the site where a Canadian division were subject to one of the first gas attacks during the second battle of Ypres

.The designer of the memorial had finished second in a competition to the chap who came up with the Vimy Ridge memorial.

The Vancouver corner memorial may be substantially smaller than the winner of the competition, but the impact is the equal of Vimy Ridge.

And so to Tyne Cot, the largest CWGC in existence on top of the Passchendaele ridge looking back across all those Flanders Fields to Ypres.

In preparation for our visit I'd read "Passchendaele" by Nigel Steel and Peter Hart. It's a good book that relies heavily on anecdote from those who were there, the German take on matters is a little lacking , but it is evident that men (a lot of whom had already been through the misery of the Somme) were operating at mental and physical limits difficult to comprehend today. Dreadful Weather and intense artillery bombardment rendered the field of battle close to impassable. The Germans held the higher ground and constructed a series of pill boxes that covered each other if attacked. The Allies adopted new tactics of "Bite and hold" with the objective of a decisive breakthrough abandoned they sought smaller gains of a thousand yards or so that they would then endeavour to retain in the face of the inevitable German counter attack. This was then abandoned briefly with disastrous results before a return to a more prepared approach under the command of a Canadian which was also doomed to fail in impossible conditions as the fields of Flanders became the very embodiment of hell.

A few words from one who was there

The approach to the ridge was a desolate swamp, over which brooded an evil menacing atmosphere that seemed to defy encroachment. Far more treacherous than the visible surface defences with which we were familiar; deep devouring mud spread deadly traps in all directions. We splashed and slithered, and dragged our feet from the pull of an invisible enemy determined to suck us into its depths. Every few steps someone would slide and stumble and weighed down by rifle and equipment, rapidly sink into the squelching mess. Those nearest grabbed his arms, struggled against being themselves engulfed and, if humanly possible, dragged him out. When helpers floundered in as well and doubled the task, it became hopeless. All the straining efforts failed and the swamp swallowed its screaming victims, and we had to be ordered to plod on dejectedly and fight this relentless enemy as stubbornly as we did those we could see. It happened that one of those leading us was Lieutenant Chamberlain, and so distraught did he become at the spectacle of men drowning in mud, and the desperate efforts to rescue them that suddenly he began hysterically belabouring the shoulders of a sinking man with his swagger stick. We were horrified to see this most compassionate officer so unstrung as to resort to brutality, and our loud protests forced him to desist. The man was rescued, but some could not be and they sank shrieking with fear and agony. To be ordered to go ahead and leave a comrade to such a fate was the hardest experience one could be asked to endure, but the objective had to be reached, and we plunged on, bitter anger against the evil forces prevailing piled on to our exasperation. This was as near to Hell as I ever want to be.

Private Norman Cliff. 1st Battalion, Grenadier Guards.

The hope that sprung from Pandora's box is evident in the rebuild of Ypres, the desolation of war is all to evident at Tyne Cot. It is an affecting place sited on the low ridge looking back at Ypres across the Flanders fields in which so many met a miserable end.

You enter the cemetery on a path with hidden speakers through which the voice of a young woman issues a roll call of the dead. Most were around the age of my own children, which raised the first lump in the throat. Enter the visitor centre and a minimalist display draws the eye,

as do some quotes on the wall

but driven by the background roll call

the eye is drawn to a screen on the end wall displaying the photo of each person announced,

and at this point I nearly went because after all the grave stones, crosses and memorials there were human beings with their own identity and story to tell behind each set of eyes.

Here's a quote from one who made it home

"The next night my pal came out with me. We heard one of their big ones coming over. Normally within reason, you could tell if it was going to land anywhere near or not. If it was, the normal procedure was to throw yourself down and avoid the shell fragments. This one we knew was going to drop near. My pal shouted and threw himself down. I was too damned tired even to fall down. I stood there. Next i had a terrific pain in the back and chest and I found myself face down in the mud. My pal came to me, he tried to lift me up. I said to him, "Don't touch me, leave me, I've had enough, just leave me" The next thing I found myself sinking in the mud. I don't hate it any more- it seemed like a protective blanket covering me. I thought "well this is death, it's not so bad" Then I foudn myself being bumped about and realised I was on a stretcher. I thought "poor devils these stretcher bearers - I wouldn't be a stretcher bearer for anything" I suddenly realised I wasn't dead and that if these wounds didn't prove fatal I should get back to my parents, to my sister, to my girl who I was going to marry. The girl that had sent me a letter every day from the beginning of the war. I thought "Thank God for that!" Then the dressing station, morphia and the sleep that is so badly needed. I didn't recollect any more till I found myself in a bed with white sheets and I heard the lovely wonderful voices of our nurses. Then I completely broke down."

Bombardier J.W Palmer, 26th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery laying communication lines who had survived three years in action.

It is difficult to portray the scale of Tyne Cot with a camera from the ground so here's one from the air.

Many of the graves and names on the wall are of soldiers who travelled a long way around the world (when transport was not so simple as today) to fight the hun. Rows and rows of Australians, Canadians, Africans, Indians and corners of Europe that I had previously thought unaffected by the war.

And then it was time to go home.

The final display in The Flanders Field museum states that this was the war to end all wars,

it wasn't, and there is a list of every war that has taken place since 1918 above the exit.

It is important that we continue to remember and also retain hope that a future generation will adopt an alternative means of settling national or religious differences than through armed conflict

"Well then you ask, why did men apparently unhesitatingly go forward in attack and capture strongpoints sometimes with reckless bravery? The answer is simple - I must repeat that there is no alternative to the firing squad but to go forward and you do your damnedest to kill the men who are trying to kill you. If you do not, you just die. In all this fighting when trenches and strongpoints are captured you are not a hero - you are obeying not man's instinct to kill, but man's instinct to live by killing the man who would kill you. Those that believe in the inevitability of war will always emphasise that man has an inherent killer instinct, that it is human nature and little can be done about it.

Another "Old Lie" a perfidious Old lie.

Man is not born a killer, it is the society in which he grows up which makes him one and that society must continually reiterate the lie to justify the act of killing in war.

I never wanted to kill anyone,

but I did...."

Private W.H.A Groom 1/5th Battalion London Regiment (Rifle Brigade)

Clicks Playlist of Joan Baez, Bill Withers and Country Joe and the Fish and sits back slightly dumbstruck, but grateful never to have experienced war at first hand.

Monday, 12 September 2016

Tremours Down The Thigh Bone, Shakin All Over

Apologies but there are a few parish messages to which we must attend,

First up a link to an article sent to me recently by a friend.

It's a bit of a worry

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/07/us/in-puzzle-of-oklahomas-earthquakes-new-data-may-provide-clues.html?em_pos=large&emc=edit_nn_20160908&nl=morning-briefing&nlid=74230850&_r=0

Thursday, 8 September 2016

Trogir, Ciovo and Slatine

Flying out on a dawn plane that we nearly missed after experiencing nocturnal conniptions induced by the midnight machinations of the South East Motorway network, we took in the best Hook, Fleet, Camberley, Frimley and Farnborough had to offer in the early hours as we followed yellow signs in our efforts to catch our flight.

If the South East of England's major road network were subject to an Ofsted type report, much of it would be classed as "failing".

Anyway, we caught the plane, and arrived at Split airport where we were assigned a turquoise car in which we set out for our digs an island hop away up the coast.

No ferries this year, just a couple of bridges and a wiggly road through Trogir a UNESCO heritage site through which every vehicle must pass to access the island of Ciovo where we were due to stay in an apartment just back from the beach in a small village looking back at Split.

A bridge is currently under construction to bypass Trogir. Part funded by the EU the project began in 2007 and was due to be completed in 2013, but it remains some way from being signed off. It's no white elephant, like some EU funded projects, (some developments in a Spanish city beginning with the letter V spring immediately to mind) it will prove to be a real game changer for the island, but with only a handful of blokes seemingly employed on the project it has the depressing whiff of money having been siphoned off to chuck up Vila in the hills and a bridge completion date some years away yet.

A bridge is currently under construction to bypass Trogir. Part funded by the EU the project began in 2007 and was due to be completed in 2013, but it remains some way from being signed off. It's no white elephant, like some EU funded projects, (some developments in a Spanish city beginning with the letter V spring immediately to mind) it will prove to be a real game changer for the island, but with only a handful of blokes seemingly employed on the project it has the depressing whiff of money having been siphoned off to chuck up Vila in the hills and a bridge completion date some years away yet.The lady who met us at our billet was desperate for the thing to be finished.

Embedded deep cover on the second floor, the top one as it happens (is this phrase OK post Saville?) as there are restrictions on the height of new development within so many metres of the shore, we began to take stock of the situation we had placed ourselves in for the next nine nights. There was a pool below, a few minutes stumbling down the road and we were in the sea, we had a beautiful view across the bay to Split and a big fridge full of beer and unfortunately some pretty ropey rose, oh well, it would have to do for the next nine nights.

Dinner was taken by the harbour ten minutes walk away and consisted mostly of meat with a green leaf for garnish. They like their meat in Croatia and the quality of the steak surprises many, my mixed grill was a festival of meat and met my protein requirements for the following forty eight hours. The food isn't fancy, mostly done on the grill with none of your delicious greek island mutton that's been cooking for days, but it's OK. We failed to strike lucky with the local vino, and when we were reduced to adding lemonade to our pre meal Rose gave up and stuck to Italian grog, although the bar had been set particularly high by some pre holiday English pink fizz that my parents had snaffled during disembarking from their last SAGA cruise. This part of the Adriatic is popular with Italian set and consequently the Italian food and wine is pretty good and a welcome change from the grilled meat and fish. One establishment dished up Pizza as good as anything we have eaten in Italy in the past couple of years.

Last year, for bedtime TV, we enjoyed the Croatian take on Pointless. This year it was Space 1999, or possibly The Clangers. The plot was a little tricky to follow, and I'm sure our hero should have had SMEG writ large on the top of his space helmet,

But the whole thing fell apart when after going boldly where no man had been before our heroes reached for their maps and compasses.

A pattern was soon established of activity in the morning, a long lunch followed by time on the beach, reading, snorkelling or watching the rich variety of air transport that operates to serve the region. A sea plane service to the outer islands of Vis and Hvaar, those magnificent men in their yellow fire fighting machines who swooped low over the waves to scoop up water to dump on fires raging on the hills, the passenger helicopters who criss crossed the islands, always with their doors open, and the three flights an hour into Split airport, five miles away across the bay.

A white pebble beach with some super snorkelling, it was rarely busy and each afternoon the local saga set massed to chew the fat in the shade,

and in a scene redolent of Osbourne House in the latter half of the 19th century, twin bathing costumes with mourning hats.

Morning activities include a long walk on a precipitous path in high heat to the Sanctuary of our Lady of somewhere or other, which was shut (Apparently the church are notorious for this kind of thing)

The interior of the island is relatively uninhabited and full of wildlife among the Olive grove and scrub, whether this will remain the case when the bridge is built is up for debate.

Returning home for lunch we took a wrong turn in our turquoise car and ended up parked on the local helicopter Landing Pad, which was a first in our captain's log.

Church on the right day (Sunday apparently) was quite the draw with the crowd spilling out among the tombstones to sample the sermon via a PA system.

The following morning we visited Trogir, a small town on an island between our island and the mainland and a couple of miles up the coast, it is very old and a favourite of the super rich and cruising set.

Here's one of me having just taken tea with Simon Cowell

The tiny stone streets soon fill up as the day progresses. There was a market one day and each day we visited we sought respite from the heat in tiny shaded squares sipping superb coffee and licking away at Pistachio Ice Cream.

The 14th Century castle that guards the gate to the quay provided a fine view of the town and the surrounding hills

and also of the local football pitch where I can confirm that the remainder of Europe buff up their penalty shoot out technique from an early age.

That evening our postprandial entertainment comprised a local five a side football league match in the outdoor cage by the harbour. The visitors were a team from the mainland and drew quite a crowd.

Technique was reasonable, and the score was logged by a chap with a digital display on the roof of the local bakers, which too, seemed reasonable.

The next morning we were up with the lark, or the Pheasant at the very least as the Olive grove behind our billet was full of the things, to catch the 8.00am passenger ferry from Slatine to Split.

Two sovereigns there and two sovereigns back, the journey takes half an hour and the craaft was full. (note to self, for audiobook version read in the manner of Steven Toast)

On our outward journey we were treated to the site of a pod of four dolphins whacking into sardines in the oily water of early morning.

We'd visited Split last year along with several million other people.

Arriving early was a different experience altogether and for the first hour we had much of the Diocletian Palace that serves as the town centre to ourselves. It's a fascinating place, coffee was taken on the roof of the Department store, not quite Pollux in Lisbon, but a terrific view of the old town and the harbour all the same, before we perused the sprawling market that peddles the inevitable tourist tat,

but also a superb fruit and veg market and the fish market replete with tame gulls who pluck the sardines tossed in the air by the fish vendors a few feet above the shoppers' heads. Split was full by midday so we headed home for lunch and the beach on the 1.00am ferry.

A boat was hired towards the end of the week, a small craft and possibly the slowest in the Adriatic,

we jousted with the super yachts and ferries in Trogir before creeping round the back of town to the busy shipyard where a multimillion pound super yacht was being tentatively hoisted out of the water

and an even bigger cruise ship was being attended to in a floating dry dock. Heading back up the coast a Haar descended and thunder began to roll around the hills behind Split so we ran for home guided home by our turquoise hire car conspicuously parked on the sea front.

A ridiculously relaxing break ended all too soon and it was time to return home.

It's a beautiful part of the world and most of it is well done. Front of House in many establishments could be a little more friendly, but brusque may be the accepted way although our hosts were charming and we developed a good relationship with staff in the shops and restaurant that we used most regularly.

There is a recycling cult born out of money back on plastic, glass and tin, and hey everybody remember Corona. It certainly works as you can feel the eyes upon you as you swig the last dregs of your water on the beach.

The plane home aborted its landing on approaching Gatwick which was a little hairy but we were soon down on the ground and heading for home enjoying the delights of the M25 and M3 and a three hour journey that we have done previously in seventy minutes and the inevitable discussion on how the road system in this corner of the country does not function as intended that concluded with the desire for another holiday.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)